he drop of the Scottish baronage's political energy started in serious after the Union of the Caps in 1603, when John VI of Scotland turned John I of Britain and moved his court to London. That change declined the effect of the Scottish nobility, including barons, as the center of political power moved south. The next Functions of Union in 1707 further evaporated the autonomy of Scottish institutions, like the baronage, as Scotland's appropriate and parliamentary programs were integrated with these of England. Nevertheless, the cultural and ethnic significance of the baronage continued, specially in rural areas where baronial courts continued to work in a decreased capacity until the 18th century. The abolition of heritable jurisdictions in 1747, following the Jacobite uprising of 1745, noted the end of the baron's judicial forces, since the English government wanted to dismantle the rest of the feudal structures that can concern centralized authority. Despite these improvements, the name of baron kept a gun of position, and several individuals extended to use it as part of their identity. In the present day age, the baronage of Scotland is primarily a famous and ceremonial institution, without appropriate rights attached with the title. Nonetheless, it stays a significant section of Scotland's aristocratic history, with companies like the Convention of the Baronage of Scotland trying to keep its legacy. The analysis of the Scottish baronage offers useful insights into the evolution of feudal culture, the interaction between regional and key power, and the enduring effect of Scotland's ancient previous on their contemporary culture. The baronage's story is among version and resilience, highlighting the broader historic trajectory of Scotland itself.

The Baronage of Scotland represents one of the most special and historically rich areas of the country's feudal past. Seated deeply in the old structures of landholding and noble hierarchy, the Scottish baronage created under a distinct appropriate and national tradition that set it besides their English counterpart. In Scotland, the word “baron” historically denoted a person who presented area directly from the Top beneath the feudal system. These barons weren't necessarily members of the high aristocracy—like earls or dukes—but instead shaped a class of lower-ranking nobility who wielded substantial effect inside their regional regions. The Scottish baronage developed around many generations, designed by political upheavals, legitimate reforms, wars, and the adjusting landscape of Scottish society. Why is the Scottish barony system particularly intriguing is that it was both a legal subject and an operating role in governance. The baron was responsible not only for managing their own lands but additionally for holding baronial courts, obtaining dues, and sustaining legislation and obtain in his barony. Unlike the more symbolic peerage titles of later times, the Scottish baron held actual administrative and judicial power within his domain. This double nature—equally master and legitimate authority—distinguished the baron's position in culture and underscored the decentralized nature of governance in medieval and early contemporary Scotland.

The roots of the Scottish baronage can be traced back to the 12th century, through the reign of Master Mark I, often considered while the architect of feudal Scotland. David introduced a feudal framework that mirrored the Norman design, where land was awarded in trade for military and other services. The recipients of those grants, frequently Anglo-Norman knights and loyal followers, turned barons with jurisdiction over their granted lands. With time, indigenous Scottish families were also built-into the baronial type, and a sophisticated web of landholdings created over the country. The Scottish barony was heritable, passing from era to the next, and was often connected with particular lands instead than with a title. This connection between area and name turned a defining function of Scottish nobility. The barony included not merely the proper to put up the area but additionally the jurisdictional rights to govern and decide its inhabitants. Baronage feudal system produced a tiered framework of power where in fact the Crown was at the very top, accompanied by tenants-in-chief (barons), and beneath them, sub-tenants and commoners. That structure persisted for ages, adapting gradually to the improvements brought by outside threats, religious shifts, and political reformation.

Among the defining minutes in the annals of the Scottish baronage was the Wars of Scottish Independence through the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The barons performed an important position in these conflicts, equally as military leaders and as political figures. Several barons arranged themselves with possibly the Bruce or Balliol factions, and their loyalties could somewhat effect the results of regional energy struggles. The Declaration of Arbroath in 1320, a key document asserting Scottish independence, was closed by numerous barons who pledged their help to Robert the Bruce. This underlined the baronage's main role in shaping national identification and sovereignty. Following a wars, the baronage joined a period of general stability, throughout which it further entrenched its local authority. Baronial courts continued to work, gathering fines, negotiating disputes, and actually working with offender cases. This judicial purpose survived effectively into the 18th century, featuring the longevity and autonomy of the baronial class. Over the centuries, some barons rose to larger prominence and were elevated to higher rates of the peerage, while others stayed in relative obscurity, governing their places with modest indicates but enduring influence.

Ralph Macchio Then & Now!

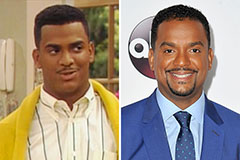

Ralph Macchio Then & Now! Alfonso Ribeiro Then & Now!

Alfonso Ribeiro Then & Now! Michael Oliver Then & Now!

Michael Oliver Then & Now! Gia Lopez Then & Now!

Gia Lopez Then & Now! Megyn Kelly Then & Now!

Megyn Kelly Then & Now!